Over the past fifty years, during periods when social struggles for emancipation intensified, and the capitalist accumulation regime fell into crisis, revisiting Marx has repeatedly emerged as a focus. Today, efforts to understand capitalism's fundamental dynamics through Marx’s analyses, assess social struggles, interpret them meaningfully, anticipate future developments, and formulate new insights remain essential. Marx remains relevant as a foremost thinker and interpreter of capitalist modernity and a theorist of the oppressed’s self-liberation through their own strength and struggle. While the capacity of Marx’s analyses to directly guide contemporary struggles for social emancipation has been naturally impacted by shifting global conditions, his work remains an essential foundation for examining the economic-political conditions underpinning these struggles.

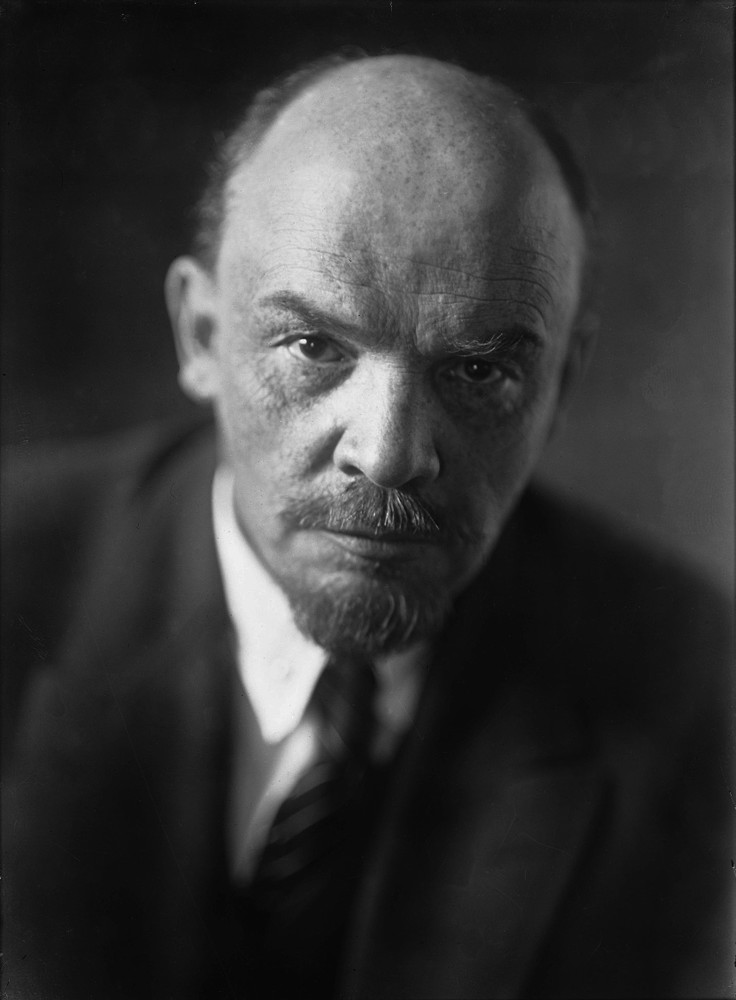

In contrast, any proposal to return to Lenin a century after his death encounters a different challenge: the weighty legacy of prolonged power practices, the “Leninist” party doctrine, and the governance style of Leninist and Marxist-Leninist communist regimes—the so-called “real socialism” that followed the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. This legacy is not only comprised of Leninist policies and doctrines implemented in Lenin’s name after his death. Much of Lenin’s theories, strategies, and approaches to power also create obstacles to returning to his ideas today. Nevertheless, those who continue to uphold Lenin's teachings, and particularly his practices, emphasize the urgency of revolution, commitment to revolutionary goals, and the conviction that insurrectional methods hold supremacy over the “rules of bourgeois democracy.”

***

Under the specific economic, political, and cultural conditions of Tsarist Russia, Lenin envisioned, fought for, and eventually achieved power with the aim of social transformation and socialist revolution. However, today's aspirations for emancipation and social revolution must be separated from Russia’s unique historical context and Soviet practices. Lenin’s works, his party, and his concept of power—inseparable from this legacy—must be examined not only through his leadership in the October Revolution’s success but also in light of the power dynamics that emerged in its aftermath. Lenin’s 1902 advocacy for a vanguard (outlined in What Is to be Done?), which views the revolutionary cadre as the primary social actor responsible for imparting class consciousness to the working class and parts of the peasantry, presents a stark contrast to ideals of self-liberation and human development. In this model, the social transformation dynamic is replaced by the political drive of a disciplined, militaristic vanguard striving for power. This authoritarian approach ultimately hinders genuine emancipation due to the despotic nature of the post-revolutionary process, creating a significant barrier to liberatory struggles.

Lenin’s revolutionary absolutism led him to achieve an unforeseen success in the October Revolution—a socialist revolution—but also laid the groundwork for a prolonged, state-controlled party dictatorship, setting the revolution on an authoritarian path from which it would never escape. Initially pursued as a “temporary” measure due to pressing necessities, this despotic path soon became dominated not by the revolution’s original goals but by the demands of the path itself. This represents a tragedy not only for Lenin but also for the world’s first successful socialist revolution.

Bolshevism emerged from the gap between this revolutionary voluntarism’s design for power and the concrete realities of Tsarist Russia’s early 20th-century social structure. While it arose from multiple sources, Bolshevism was largely Lenin’s creation. Thus, returning to Lenin today would mean returning to the Bolshevik vision and practices. Undeniably, this vision and these practices—particularly Lenin’s personal effort, persistence, and foresight in achieving the “Second Revolution” of October 1917—ushered in a new chapter in 20th-century history. Yet both Leninism and specific principles and practices championed by Lenin contributed significantly to the eventual collapse of this ambitious experiment in global freedom and equality, leaving behind a predominantly negative legacy after three-quarters of a century.

In a 1939 article, Boris Souvarine, who authored the first comprehensive critical book on Stalin, encapsulated post-Lenin Soviet practices: “Lenin is dead, and his body embalmed. Leninism is dead and buried. The Leninists died slaughtering each other and losing their honour. A tsarist regime incomparably worse than the previous one was installed. The previous one was, at least, not totalitarian. If Lenin had been able to look on from his Asian mausoleum at this picture, which he had not foreseen, he would certainly not have been proud of his work.”

While Souvarine distinguished Lenin from Stalin’s totalitarian practices, he still noted a continuity between Lenin and Stalin, stating:

“The Bolsheviks, from Lenin to Stalin, first of all, favored socialist freedom over police coercion. They believed they could achieve through evil. Then, they turned necessity into virtue. Inside, they made the brutal practices of war the rule of peacetime. So they have turned dictatorial habit into a second nature.” [1]

There is little doubt that Lenin would have been dismayed by the regime established in his name and the practices of Stalinism. In the last two years of his life, Lenin had a partial, if vague, sense of this unfavorable trajectory and expressed concerns about the bureaucratization of power. However, it is worth noting that Rosa Luxemburg had argued, long before and against Lenin, that the principle of democratic centralism was, in reality, a form of bureaucratic centralism. Lenin, however, never acknowledged a link between party bureaucratization—and consequently, state bureaucratization—and democratic centralism. From his letter known as his “testament,” which the CPSU Politburo members carefully concealed for years, we know that his primary concern in late 1922 was the internal discord among the Russian Communist Party’s leading cadres, particularly Stalin’s harsh, repressive behavior. Furthermore, along with implementing the New Economic Policy (NEP)—a policy he had supported as early as 1918, though initially blocked by party leadership—we see from several of Lenin’s writings and letters in 1922-1923 that he had started to recognize Russia’s lack of social maturity, economic development, and civilized principles necessary to sustain a socialist revolution.

Lenin, meanwhile, established an intelligence and security organization—the precursor to Stalinism—just a month after the October Revolution. The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage, or Cheka, was created by a decree issued by Lenin. In many respects, it functioned as a continuation of the Tsarist Ohranka (Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order), which had similarly aimed to suppress revolutionary activities. On December 7, 1917, Lenin described the Cheka as “the supreme weapon for the realization of the will of the proletariat” and declared that “the Cheka must be the centralized will of the proletariat.”

At the 9th Congress of the CPSU on April 3, 1920, Lenin concluded the debate on cooperatives with a sharp statement that seemed to cut through all complexity: “A good communist is also a good Chekist.”[2] This belief became a cornerstone of Stalinism. By 1920, proletarian members constituted just over ten percent of the Russian Communist Party. By contrast, a quarter of the party members belonged to the Cheka or the Red Army. If the “supreme weapon” for realizing proletarian will was the intelligence and secret police, and if this organization embodied a “centralized form of proletarian will” in a state-party apparatus, the path to a despotic security state was, in today’s terms, inevitable. Implemented with the approval of most Bolshevik leaders, these policies planted the seeds of the Siloviki state, whose legacy remains visible even after the Soviet Union’s dissolution.

The practice of concentration camps, which would later evolve into Stalin’s Gulags, also originated under Lenin’s orders. In August 1918, amid resistance and uprisings that preceded the civil war, Lenin instructed a Cheka officer to establish a concentration camp in the Penza region, where “a merciless mass terror of kulaks, priests, and white guards will be inflicted.” Notably, the term used was “mass terror”! This concept of terror was not confined to the early months of the revolution or the civil war period. In May 1922, as the new penal code was being drafted, Lenin remarked that its purpose was to solidify the power of the party-state apparatus. He stipulated that the guiding principle for the courts should be that “terror must be clear and justified”!

In late 1917, Lenin ordered “the cleansing of Russian soil from all harmful vermin.” Terms like “purification,” “cleaning,” and “culling” were frequently used by Lenin to describe the elimination of groups he labeled as “fleas, bedbugs, lice”—the language he employed to endorse and encourage internal purges. For Lenin, such internal purification was essential for the revolutionary party. The quotation he chose from Lassalle’s 1852 letter to Marx, placed at the start of What Is to Be Done? in 1902—” The party is strengthened by purifying itself”—served as a precursor to the party and state practices he later directed. Purification, weeding out, and purging were key aspects of the Bolshevik Party under Lenin. While these measures were limited to exclusion and division during his time, they avoided physical annihilation. Under Stalin’s absolute rule, however, these practices transformed into something far more brutal and bloodier. On the eve of World War II, over three-quarters of the founding CPSU cadres were “purged” and physically eliminated.

Lenin’s vision of the party closely aligned with what would later be known as Leninism. He saw the party as an organ of power composed of revolutionary professionals wholly dedicated to the party’s goals and functioning as rulers on behalf of the proletariat. The 1918 constitution of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic explicitly defined the party’s role: “The Communist Party directs, controls, and dominates the entire state apparatus.” This definition, albeit in different forms, remained valid until the Soviet Union’s collapse.

The Constituent Assembly, however, was dissolved in early January 1918, before the new constitution’s adoption in July. After right-wing socialist revolutionaries and Mensheviks left the Second Congress of All-Russian Soviets on the night of October 25, Lenin’s revolutionary manifesto, read aloud by Lunacharsky, called for a Constituent Assembly of deputies elected by universal suffrage—a vote that took place in the final two months of 1917. But this Constituent Assembly convened for only a single day in January 1918. In this election, which saw 47 million voters participate, the Bolsheviks received just 22% of the vote, while the Socialist Revolutionaries—supported primarily by peasants—won nearly half. The Liberal Party, which had briefly governed Russia after the February Revolution, gained less than 5%. Although the Bolsheviks held a minority position, the assembly comprised a broad majority of revolutionary and socialist factions. In its one session, the Constituent Assembly opposed the Bolshevik takeover and declared the formation of a Democratic Federal Republic of Russia. Early the next morning, after a Red Guard sailor announced, “The guards are tired; leave the hall,” the Assembly chairman hurriedly passed several resolutions and adjourned the meeting. The following day, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, led by Kamenev, formally dissolved the Constituent Assembly. Lenin had forewarned that “any attempt to treat the Constituent Assembly in formal and narrow legal terms is a betrayal of the cause of the proletariat.” He later claimed the election lacked legitimacy, as “the electoral lists were drawn up two months before the October Revolution” and failed to reflect the “real strength” of the Bolsheviks, asserting that the Russian working class had not yet developed sufficient consciousness. On these grounds, Lenin and the Bolsheviks concealed their minority defeat and effectively annulled the election results.

Lenin espoused the idea that “there can be no revolutionary practice without revolutionary theory.” Yet, he also consistently adapted the theory to fit practice, guided by the principle of “concrete analysis of the concrete situation.” In truth, Lenin was not so much a theoretician as a man of action, prioritizing strategy over abstract theory. For Lenin, theory often served as a means to justify strategy. His ostensibly theoretical writings were primarily focused on answering the immediate questions of how to seize and maintain power. For instance, just two months after he presented a nearly anarchist view on the dissolution of the state in The State and Revolution, Lenin—now with the Bolsheviks in power—took decisions that directly contradicted this vision, endorsing a party dictatorship on behalf of the proletariat. This shift was driven by his revolutionary voluntarism, a legacy of the Narodnik tradition’s urgent desire to overthrow Tsarist despotism as quickly as possible. Recognizing the social structure’s limitations, Lenin sought to overcome these with the same voluntarism that had fueled the overthrow of the Tsarist regime, substituting the vanguard’s will for the broader social will. Lenin was not alone in endorsing this approach; all the Bolsheviks eventually embraced it, even if reluctantly at times. Trotsky, for example, often voiced reservations about Lenin's “excessive harshness, Jacobinism, and Robespierrian tendencies.” Though he distanced himself from Lenin and the Bolsheviks for extended periods, Trotsky ultimately joined the Bolsheviks and, once in power, became a staunch adherent to their methods.

On the one hand, Lenin was an orthodox Marxist and, on the other, a continuation of the Narodnik tradition—an insurrectionist with a drive for modernization and Westernization who opposed the Tsarist regime and aristocracy. At the same time, he was an organizer who did not separate political struggle from the pursuit of power. A highly creative strategist, Lenin sought a political solution for every situation, readily abandoning orthodox positions he had previously defended if a change in strategy required it and then formulating and championing a new orthodoxy. He was also a formidable polemicist; Rosa Luxemburg famously described him as “a fighting cock.” Some Mensheviks, sarcastically, and even some Bolsheviks, reproachfully, noted that Lenin “used his pen like a shotgun.”

War and the logic of war played a significant role in Lenin’s strategic thinking. He applied Clausewitz’s theory of war to class struggle, viewing war as a moment when capitalism’s internal contradictions intensified and imperialist conflicts sharpened. Yet he also recognized that war could undermine revolutionary potential, as seen with the working masses of Germany and France who marched to the front in World War I with patriotic fervor. To counteract this, Lenin stressed the need for revolutionary leadership. If war was simply an extension of politics, a “revolutionary subversion” in the aggressor nations could transform inter-imperialist war into civil war. In such conditions, a disciplined, cohesive vanguard party, organized with military precision, could seize power on behalf of the proletariat.

The revolutionaries who founded a party to bring class consciousness to workers from outside the economic struggle needed to be well-versed in techniques of secrecy and conspiracy. However, Lenin’s concept of conspiracy differed significantly from the individual acts of violence and assassination often employed by Narodnik circles in Russia. Not only did Lenin disapprove of these actions, he also publicly criticized them. For Lenin, the necessity of conspiracy meant that professional revolutionaries operating under the severe repression of the autocratic regime had to understand and strictly adhere to secrecy. Conspiracy, for Lenin, also extended to organized bank robberies to secure the funds necessary for revolutionary activities. It should be noted, however, that before coming to power, most of the party’s funding came not from robberies but from donations and grants provided by wealthy individuals who supported the struggle against Tsarism.

In 1914, when Lenin advocated “the right of peoples to self-determination” as a revolutionary slogan, he argued that “there is a democratic content in the bourgeois nationalism of every oppressed nation.” For him, the national question and the right to self-determination were consistent with the pursuit of democratic gains. “It would be a mistake to believe that the struggle for democracy would distract the proletariat from the socialist revolution,” he said in 1914. “It is impossible to imagine a victorious socialism which does not realize full democracy,” he claimed. “The proletariat cannot prepare for victory over the bourgeoisie unless it wages a revolutionary and systematic general struggle for democracy.”[3] However, five years later, in his Theses on Bourgeois Democracy and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, presented at the founding congress of the Third International, Lenin endorsed a system integrating legislative and executive powers, restricting press freedom, and organizing electoral districts by factories and workplaces—what he termed “full democracy.”

***

Lenin’s strategic genius lay not only in recognizing that Russian workers and peasants had grown deeply weary of the war—more keenly than other revolutionaries, including many within the Bolshevik ranks—but also in uniting the demands of the vast peasant majority for land with those of industrial workers for fair working and living conditions, under the “promise of an immediate armistice.” The rallying cry of “peace, bread, land” became the foundational principle that paved the way for the October Revolution. The slogan “All power to the Soviets” and its actualization completed this strategy. Lenin’s ability to adopt and steadfastly advocate for this approach was made possible by the emergence of autonomous peasant and workers' councils, which, in the face of a crumbling Tsarist regime unable to maintain control, had started to manage daily life independently—just as they had during the 1905 revolution. Lenin exploited this dual-power situation, even while in Finland, avoiding arrest by the Kerensky government, ordering Trotsky to prepare for an uprising.

The provisional government’s failures after the February Revolution—its inability to address the fundamental demands of workers’ and peasants’ soviets, the months-long delay in declaring a republic even after the fall of Tsarism, and its reluctance to pursue an armistice despite widespread demands among soldiers—quickly bolstered support for the Bolsheviks, especially within the Petrograd and Moscow soviets. It is crucial to emphasize that a powerful dynamic of self-liberation, which had begun well before 1917 and peaked that year, was realized through the soviets and the initiatives of workers and peasants. Both the February and October revolutions drew their leading social energy from these grassroots movements. In this context, Lenin skillfully merged this social momentum with the Bolshevik Party’s dynamism, creating a potent strategic alliance that proved effective, albeit for a relatively brief period.

The Bolshevik occupation of the Winter Palace by the Red Guard, driven by Lenin’s insistence, was indeed a coup d'état, but it also marked the culmination of a prolonged struggle since Lenin’s return to Russia. In the weeks leading up to October 25, rumors of an impending Bolshevik “exit” (vistuplenye) were widespread in Petrograd. Plekhanov, for example, remarked that although he “didn’t expect vistuplenye to occur precisely between October 20 and October 25 (November 2 and November 7), as anticipated, but he was certain it would happen before November’s end.”[4] During the night of October 24–25, Trotsky summarized the situation at the 2nd Soviet Congress, stating, “What has taken place is not a conspiracy, but an uprising. The uprising of the masses of the people needs no justification. We have steeled the revolutionary energies of the Petrograd soldiers and workers. We have clearly molded the will of the masses to rise up, not conspire.”

Once in power, the Bolsheviks rapidly enacted decisions that would serve as precedents not only for Russia’s liberation struggle but for liberation movements worldwide. The Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom)[5], composed of 15 Bolsheviks, was tasked with governing from the morning of the October Revolution until the Constituent Assembly could convene. These initial actions represented Lenin and the Bolsheviks’ commitment to swiftly and comprehensively modernize Russia.

On the morning of October 26, a call went out to “all workers, soldiers, and peasants,” demanding “an immediate democratic peace and an armistice on all fronts.” Other proposals included transferring land from large landowners to peasant committees without compensation, democratizing the army, establishing workers' control over production, and recognizing the right of self-determination for all the peoples within Russia. It was also suggested that a constituent assembly be convened as soon as possible and elected by universal suffrage to draft a new constitution to enact these principles.

The nearly one hundred decrees issued by the Sovnarkom were, indeed, harbingers of sweeping transformation. Some of these decrees expanded on fundamental rights introduced after the February Revolution, while others imposed new restrictions. After February, the death penalty had been abolished, official discriminatory practices against religious minorities (especially Jews) were eliminated, and universal suffrage and equality for all citizens had been declared. On November 8, shortly after the October Revolution, the death penalty—reintroduced by General Kornilov for front-line soldiers under Kerensky’s government—was abolished. Yet, the following day, all newspapers calling for “resistance and non-submission to the government” were banned. The standard workday was limited to eight hours. On November 15, the government proclaimed the right to self-determination and equality for all peoples within Russia.[6] Subsequently, on November 24, all imperial classes, ranks, titles, and epithets were abolished, accompanied by a comprehensive judicial system reform. The newly established Commissariat of Public Education ended the church’s role in education. Banks were nationalized, and the control of nearly a hundred large industrial enterprises was transferred to elected workers’ soviets. Religious marriage was replaced with civil marriage, and divorce was legalized. On December 29, interest payments and the repayment of Tsarist Russia’s debts were suspended. Meanwhile, in December 1917, the Constitutional Democratic Party (KD) was banned. At the first Congress of Trade Unions, held in early January 1918, the Menshevik proposal to secure workers' right to strike was rejected, with the justification that “under the dictatorship of the proletariat, the working class would not strike against itself.”

This wave of modernization persisted even after the Constituent Assembly was dissolved. In early February, state and church affairs were formally separated, and the Gregorian calendar, used in Western Europe, replaced the Julian calendar. Significant steps were also taken to advance women's rights. Finally, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed with Germany, effectively ending the war on the Russian fronts.

***

By 1922, much of the early transformative decrees issued by the Bolshevik government in late 1917 and early 1918 had faded. Following nearly four years of a brutal civil war, the Bolsheviks emerged with absolute control, but the war had intensified the party’s militarization, with terms like “militarization of labor” becoming part of the Bolshevik lexicon, mainly due to Trotsky’s influence. Pluralism—once a core value of anti-Tsarist movements—was quickly abandoned before the civil war even began. By its end, pluralism had been dismissed as a “remnant of bourgeois democracy” and deemed a “counter-revolutionary” concept. Factory committees, trade unions, and soviets—once vital to the 1917 revolutions—were subordinated to the Bolshevik Party, transformed into the “conveyor belts” of party directives, with any opposition eradicated under the “counter-revolutionary” label.

Among the enduring gains realized during the October Revolution’s fervor, besides advances in education, public health, and cultural policies, the strides made in women’s rights were perhaps the most lasting and widespread. In 1920, under the leadership of Alexandra Kollontai and with the reluctant support of Lenin, who his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, persuaded, abortion was legalized—making Soviet Russia the first country in the world to do so. Women achieved equal rights across most sectors, and many of these gains persisted. However, it remains notable that women did not reach the top leadership positions in the CPSU until the USSR’s collapse.

***

In his autobiographical work My Life, written during his exile in Turkey and published in 1929, Trotsky describes Lenin, saying, “I was politically distant from him, but it was impossible not to feel the pull of the glamour exuded by this powerful figure.” Lenin, who devoted his life sincerely and selflessly to the struggle for the working class’s emancipation and humanity’s liberation, is remembered less as a successful architect of socialism and more for his significant role in taking a transformative step toward modernizing Russia. This is also Lenin’s tragedy: he realized that, given Russia’s historical and political context, the potential for socialism—a movement to emancipate humanity and elevate civilization—was severely limited, leading him down an unforeseen path.

After all, there exists both rupture and continuity between Lenin’s lifetime actions and what was later done under “Marxism-Leninism,” formalized at the 5th Congress of the Comintern in 1924 as a global revolutionary ideology. In the USSR after Lenin’s death, this continuity was shaped mainly by the historical limitations constraining Russia’s transformation. Once in power, the determination not to relinquish control at any cost paved the way for a new despotism with the violent suppression of social mobilization.

What remains of Lenin today? Few people or movements believe in the possibility of creatively revitalizing Leninism or in its capacity to address contemporary issues. Those who tend to emphasize aspects of Leninism are largely rejected by socialist and communist circles that now embrace left-liberal political values. Such interpretations focus on a vanguard cadre replacing broader class and social movements, a military-like command structure, denial of social organizations’ autonomy, refusal to cooperate with other left/socialist groups, defense of single-party rule, and viewing democratic principles as mere bourgeois values. The goal of seizing power with rigid voluntarism conceals an underlying drive for domination.

Yet there is another legacy of Lenin—a leader acutely aware of the “socialism or barbarism” dilemma and determined to overcome the barbarism that plagued Russia and, later, much of humanity amid global war. This legacy serves as a reminder of the paths we must avoid while pursuing similar resolve in today’s struggles against rising barbarisms that threaten humanity’s future. As we ask, “What is to be done?” this legacy also illuminates the question of “What not to do?” to ensure that the fundamental socialist principles of liberation and equality are not sacrificed for the sake of “socialist power’s survival.”

[1] A member of the 3rd International from its foundation and for a time a member of its secretariat, Boris Souvarine was later expelled from the organization. In 1935 he published Staline, Aperçu historique du bolchévisme [Stalin, A historical overview of Bolshevism]. In 1977, a new edition of the book was published, which analysed the experience of the intervening forty years with an epilogue.

[2] This oft-cited piece of advice appears in a discussion about measures to address underperformance among cooperative managers. The whole paragraph is worth examining: “Comrade Shushin is right when he says that many counter-revolutionaries take cover in the co-operatives. But this is another matter. The Cheka was mentioned on the spot. If your myopia prevents you from unmasking some of the co-operative leaders, then put a communist there to point out the counter-revolution, and this good communist placed in the consumer union [co-operative] - for a good communist is also a good Chekist - will lead us to at least two counter-revolutionary co-operators.” Lenine, Oeuvres, vol. 30, p. 495.

[3] Lenin, Questions de la politique nationale et de l'internationalisme prolétarien, Moscow, 1968.

[4] Jacques Sadoul, Notes sur la révolution bolchevique, Maspéro, 1971 (first edition 1919). John Reed also mentions this in Ten Days that Shook the World.

[5] On November 4 (November 17), Kamenev, Zinoviev, Rykov, Nogin, Milyutin, and several other members of the Bolshevik Party resigned from the Central Committee “in protest against the continuation of a government composed exclusively of Bolsheviks and sustained by terror”; the last three also resigned from the Council of People's Commissars. Of the fifteen members of this first Sovnarkom, nine were later executed by Stalin between 1937 and 1940.

[6] Soon after, the Poles, Finns, Baltic peoples, Ukrainians, Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis declared their independence.