"Let's not forget that conservatism was promoted by the social engineers of the Sept. 12, 1980 regime [when a right-wing military junta took power in a predawn coup in Turkey]. Later, in the 1990s, they were afraid of the graduates of the religious schools that were created by them and have tried to prevent the spread of more of such schools. … There was a conscious effort to increase supporters for nationalism and conservatism in various ministries, the police force and at universities," he said.

İnsel, who dissects Turkish politics and society in his books and articles, said the Justice and Development Party's (AK Party) closure would cause a shock in Turkish society.

“After such a big jolt, we will see a segment of society and some voters who are sharper, more vindictive, tense and sharp. What the AK Party can do for Turkish democracy is to counter the closure case by speeding up the reform process and making all the legal changes it can within its power.”

For Monday Talk, İnsel explains the dynamics of the closure case against the ruling party.

How did the party closure case come about? When did the process start?

How we came to this point is related to the results of the 2002 election because in its aftermath, those who hoped to carry on a guardianship regime were quite disappointed. In their eyes, the AK Party should not have been able to get that much power. They portrayed this as a threat to the secular regime, but their real concern was related to the possibility of ending the guardianship regime that was revived by the 1982 Constitution. Those who believed majority rule would not be possible in Turkey were shown to have been mistaken, especially following the local elections in 2004, when the AK Party was further strengthened. In addition, we recently saw journalistic reports of how some military coup attempts were planned in 2004 -- mostly because some army generals realized that there was no alternative political party to the AK Party. So at every opportunity those who are against AK Party rule pursued a campaign against the AK Party to the extent that they created instability in the country. Their purpose was to wear out the AK Party and create an expectation in the public of emergency rule.

When was the peak in creating disorder reached?

The campaign against the AK Party reached its peak during the presidential election. The Turkish military’s April 27 e-memorandum was a part of this. The latest peak occurred when the Supreme Court of Appeals chief prosecutor filed a case with the Constitutional Court [on March 14], demanding that the AK Party be disbanded on grounds that it had become a focal point of anti-secular activities. These were attempts to ensure the continuation of the guardianship regime.

Why was the closure case not brought up before, for example, at the time of the presidential election?

We can see in the indictment that party officials have been accused of wrongdoings that took place prior to the party’s further rise to power with the July 22 election. At the time of the presidential election, a “367 criterion” [which was approved by the judicial establishment as a prerequisite for a presidential election as a result of an unusual interpretation of the Constitution] was imposed, and the expectation was that the party’s votes would decrease and the opposition Republican People’s Party’s [CHP] votes would increase in the July 22 election. Because of this expectation, the closure case was not brought up prior to the election.

Did you expect the closure case?

Personally, I did not expect it. I still had a belief in the Turkish people and institutions and thought that problems would be solved within the limits of a democratic parliamentary regime.

Is this case a first in the world?

As far as democratic parliamentary regimes are concerned, in the history of world politics, this is a first.

Have you received any out-of-country calls inquiring about what is going on?

Yes, I have. Researchers wonder what the legal basis for the closure case against a ruling political party which increased its number of votes the second time around and received 47 percent of the vote is. They wonder if this party has really been the focal point of some serious activities and if it deserves to be closed. When you say it is not, they are puzzled even more and ask, “How come?” They wonder if these activities have not been noticed in the five-and-a-half years of the government’s rule. They also wonder if the accusations are related to the words and actions of the party members prior to the AK Party’s ascension to power or when the party was ruling. It is also a new thing in the history of world politics that the case also involves the president. Because of that, researchers think the case might be a significant example for political science literature because there is a danger of rule by judges [dikastocracy or juristocracy].

Where was the rule of judges seen before and how do they rule? When can we say that Turkey is under the rule of judges?

This is a first in international literature despite social security reforms undertaken by US President Franklin Roosevelt in the 1920s which were harshly criticized by the US Supreme Court. The rule of judges is a term used when the judicial body acts as a body checking the executive branch and they work beyond their legal scope, playing the role of political arbitrator and taking sides in the political arena. In Turkey, if the fate of the president is decided by the Constitutional Court rather than Parliament, then we can say that this is a rule of judges.

Do you think the closure case might be related to the Ergenekon investigation, in which dozens of people have been detained under the suspicion that they are involved in deep state-related gangs?

I don’t have enough expertise to evaluate this, but the case is significantly independent of this investigation. We know that the chief prosecutor has been following the activities of the AK Party since 2003. It cannot only be related to the Ergenekon investigation; it has its own dynamics. When you read the indictment, you can see that he cited the government’s efforts to lift the ban on wearing headscarves at universities as one of the main reasons behind his demand for the closure of the party. The case is more connected to the headscarf issue.

What if the government has not slowed down in adopting reforms?

It has shown weakness in adopting reforms since 2005. If it had not, I am not saying that the process would be smooth and easy, and it is not very easy for society to become democratized as it does not happen with the push of a button, but the government would have been able to face criticism more easily. I think opposition to the AK Party has gained strength because the AK Party has been seen as making use of reforms to its own benefit and not that of others.

The government seems to be willing to reinvigorate the reform process. Would that help it?

They don’t have any other choice. If they defend themselves but basically accept being closed, no matter how much we criticize the AK Party, its closure would mean a suspension of Turkish democracy. Its closure would cause a significant jolt. After such a big jolt, we will see a segment of society, some voters, who are sharper, more vindictive, tense and sharp. What the AK Party can do for Turkish democracy is to counter the closure case by speeding up the reform process and making all the legal changes it can within its power. It may not be able to have a majority to change the Constitution at the moment, but it has the majority to change laws such as the law governing political parties, the law governing elections, the Turkish Penal Code’s (TCK) restrictions on freedom of speech, higher education laws and so on. There is no excuse for them not to make these changes. One feels the need to ask where they have been and if they need a threat to be able to go ahead with reforms. Would they have moved forward with reforms had they not needed to protect themselves? Are they real democrats? Indeed, these are the limits of the AK Party officials.

Could you elaborate, please?

They have been adopting democratic reforms because of the conditions they found themselves in and not because they themselves come from a democratic culture. They have been forced to adopt reforms through circumstance. It is sad that they have to be pushed to move on with the reform process. I should underline that this is the AK Party’s epistemological limit.

Is this only the AK Party’s limit?

You’re quite right; we can’t blame only the AK Party. It is a societal problem. Turkish society’s understanding of democracy has its limits.

Including the opposition?

Of course, this is another serious problem. The AK Party has found the struggle for democracy in its lap not only because of the various tests it has been through but also because of the opposition’s, especially the CHP’s undemocratic attitude. Yes, we cannot say that the AK Party is a champion of democracy, but it is among the best of the bad.

Does Turkey face the threat of a Shariah regime?

No, Shariah is not a threat in Turkey. We face a threat of military coups. On the other hand, we face an increasing trend of conservatism trying to interfere with society’s cultural codes. As I think neo-liberalism is a threat to the society, I think conservatism is a threat as well for a society which supports freedom. But these threats should have been dealt with politically within democratic limits. This should be an ideological political struggle. It should be done through persuasion.

You often make a reference to the Sept. 12 regime when you talk about conservatism…

Let’s not forget that conservatism was promoted by the social engineers of the Sept. 12, 1980 regime [when a right-wing military junta took power in a predawn coup in Turkey]. Later, in the 1990s, they were afraid of the graduates of the religious schools that were created by them and have tried to prevent the spread of more such schools. … There was a conscious effort to increase supporters for nationalism and conservatism in various ministries, the police force and at universities.

What is the plan of the social engineers now?

After the AK Party’s closure and its leaders’ elimination, they hope to have a more “harmonious” party formed so the AK Party’s heavy weight on the center-right will be dispersed. Ironically, the Sept. 12 regime created a time bomb by making it very difficult for parties to enter Parliament. We can now see that the time bomb has exploded in their own hands.

So social engineering does not work in Turkey?

It has always backfired. Either their engineering is very bad, or this is not a job to be done by social engineering. I think this is a country in which social engineering is not appropriate.

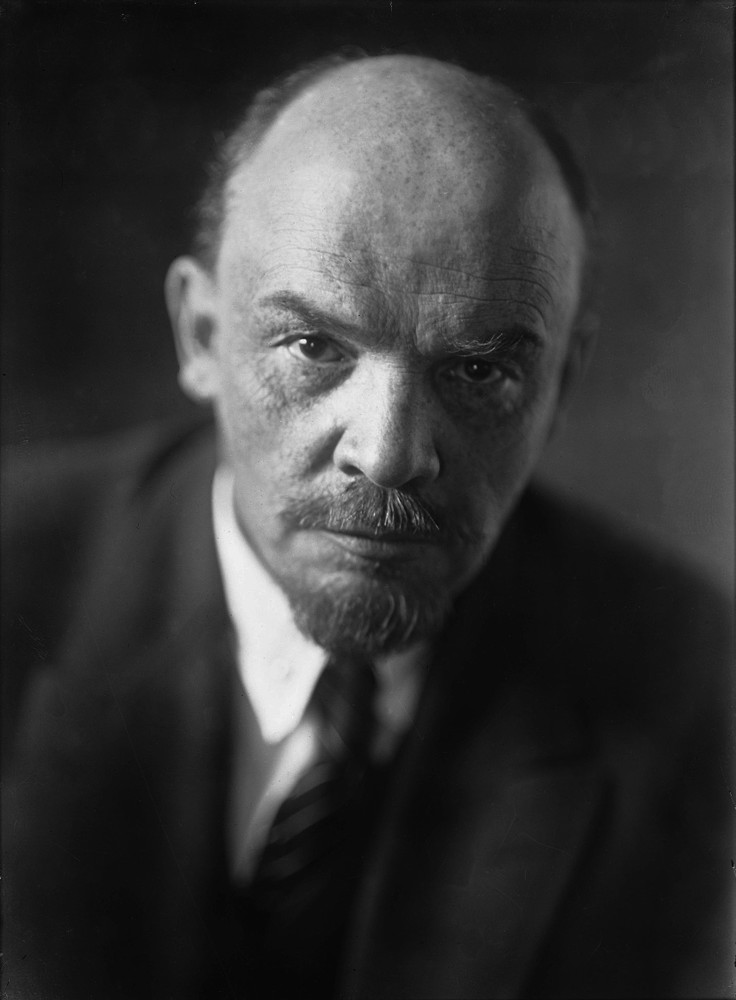

Ahmet İnsel

A professor at Galatasaray University since 2001, he has also been the head of the department of economics since 2003. Having obtained his master’s and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Paris, 1 Panthèon-Sorbonne’s department of economics, he served as vice president at the same university in 1994-1999. Since 1984, he has been a member of the board of editors at the İletişim Publishing House and the publishing board of Birikim, a monthly analytical political review.

He is the co-editor and editor of books, including “Türkiye’de Ordu, Bir Zümre, Bir Parti” (Army in Turkey; a Social Group, a Political Party) and “La Turquie et le dévelopement” (Turkey and Development) as well as the author of several books, including “Hegemonyanın Yeni Dili” (Neo-liberalism, The New Language of Hegemony) and “Solu Yeniden Tanımlamak” (Redefining the Left).

He has a weekly column in “Radikal” daily’s Sunday supplement “Radikal2.”

[email protected]

Zaman Today, 07.04.2008

Interviews

YONCA POYRAZ DOĞAN