I’m not sure how much Turkish people are aware of the seismic results of the UK’s recent EU referendum (well seismic at least for us), but my friend Barış Özkul has asked me to write a piece on this subject and hopefully some of Birikim readers will find it interesting. I shall endeavour to stick to the facts, but in a UK debate that has been so devoid of facts, it is inevitable that the piece will include my personal opinions. I would caution that there are many other opinions in the UK at the moment. We are perhaps better known currently as the disunited kingdom.

We joined the EU back in the 1970s. Back then we were taken in by the Conservative Government (soft right wing at that time) for economic reasons of developing trade relations with Europe. At that time, the Labour Party opposition (left wing) opposed our membership of the EU amidst concerns about loss of workers’ rights. This changed under the Thatcher Governments of the 1980s and 1990s - the UK left wing starting to value EU protections of workers’ rights and seeing them as a bulwark against the Thatcher/Reagan creeping neo-liberalism. At the same time, there was a growing conflict in the Conservative Party about perceived loss of control to the EU and perceptions that EU treaties were leading towards a European super state. Some of these concerns were focussed by Boris Johnson in the early 2000s as a correspondent in the Times newspaper where he initiated a negative tone towards Europe, denigrating every decision being made there. This tone became replicated by much of the UK media because it sold newspapers and pandered to a UK that harked back to the days of the country having an empire. This drip drip of hostile media led to a nationwide perception of European decision-making by unelected and unaccountable alleged “Brussels bureaucrats”.

Running alongside this has been the country’s long term love hate relationship with immigration into the UK. Without knowing the full facts on this, the UK has, at least during my lifetime, been very welcoming of immigrants from various parts of the world, but there have also been undercurrents of people who fear different people and in some cases campaign against immigrants – particularly from those of different ethnic backgrounds – resulting in some appalling evidence of racism particularly in the 1970s. However, primarily as a result of trade union activism and a change in youth consciousness, since the 1980s equalities legislation was passed initially by the Conservative Governments, but significantly extended under the Labour Governments from 1997. Nonetheless, tensions remained and whilst the Labour Government made good progress in the 2000s on issues such as education and health in some of the UK’s most disadvantaged communities, insufficient number of affordable homes were built, and it has been a simple fact that the post Thatcher Labour Governments were elected on a ticket that it would not seek to reverse the substantial UK wealth inequity that had grown since the end of the 1970s out of a perception that to challenge neo-liberalism would have made Labour unelectable. This therefore resulted in ongoing growth of a huge divide in the UK between “Hampstead and Hull” (Hampstead being a middle to upper class area of London where a number of politicians are likely to have homes and Hull being a city in north east England devastated by the loss of heavy industry).

The Labour Governments were slow to recognise the growing perceptions in working class communities that their problems were being caused by immigrants. It was probably the case that they didn’t do enough to bolster up housing, education, health and other services in areas such as the Fens (a rural area in Eastern England that had become reliant on large numbers of migrant workers) and insufficient service provision provided ample fodder for right wing anti-immigrant campaigners.

These tensions were heavily exacerbated by the global financial crisis of 2008, which also led to the incoming Conservative led Government of 2009, whose approach to tackling the national debt caused by propping up the banking sector was to impose an “austerity” regime. Part of this austerity regime was to slash public support for those on low incomes in disadvantaged communities, pouring fire onto the growing discontent in those communities. That even the Labour Party supported some of the austerity measures (out of concern that to not support them would lose them the support they would need to secure support from middle class communities to have any chance of getting back into Government), meant that the UK’s most disadvantaged communities lost hope, felt that none of the political classes were listening to them and felt any sense of identity with or had any power in our national democracy.

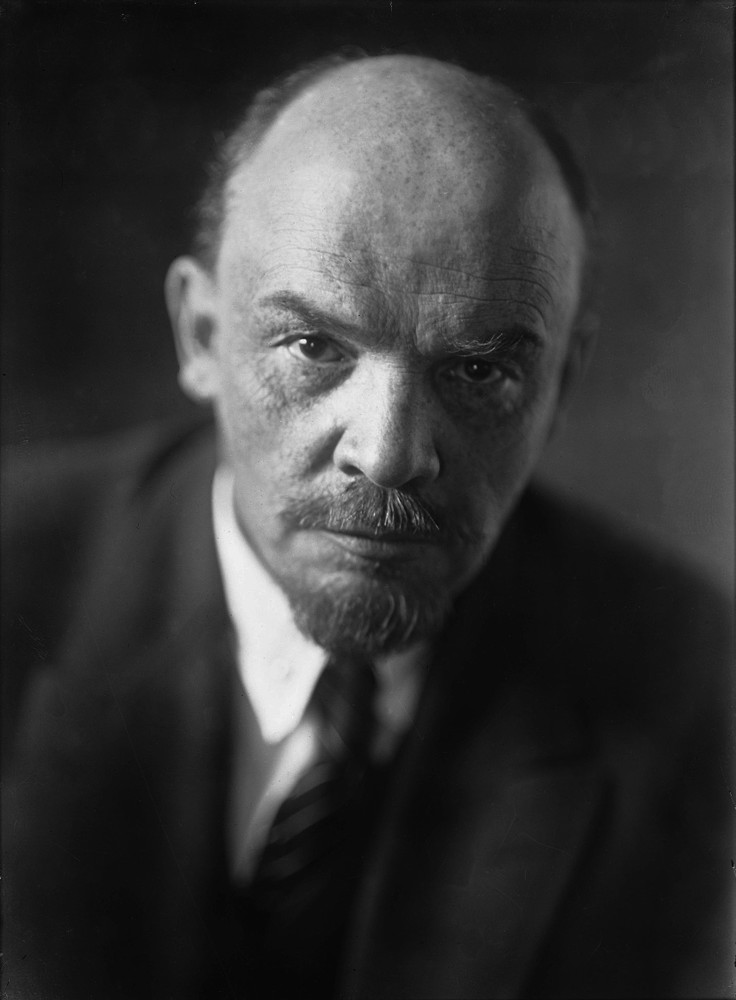

This has contributed in the UK to the rise of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), campaigning for some years to take the UK out of the EU. No one gave it any credence until the far right leadership of ex-banker Nigel Farage led to lowest common denominator politics that sought to build a platform from the fear and hate that was being generated about immigration and lack of public services allegedly as a result of immigration. My apologies here – I have probably departed from my intended objective stance and those who support UKIP would challenge my viewpoint of Farage, but my perception is that he is a racist bigot who has used his racist bigotry to exacerbate fear and hatred for his own political ends. To me, the only difference between him and Hitler is that Farage does not wear fancy costumes to emphasise his bigotry … yet.

Initially UKIP’s impact was thought to be largely amongst Conservative voters. Indeed amongst UKIP’s electoral candidates it seemed to attract a number of elderly white “Little Englander” buffoons from places like Tunbridge Wells in Kent (an affluent town that had become synonymous with letter writers to supposedly serious right wing newspapers on comparatively irrelevant issues like parking meters) who would previously have voted Conservative.

The 2015 General Election

This meant that the Conservative Party under David Cameron had to take steps to shore up its support in the run up to the 2015 General Election. Without a Parliamentary majority, the Cameron Government from 2009 to 2015 had to govern with the support of the minor Liberal Democrat Party. Their support in this coalition Government for most of the austerity measures brought in meant that they would be wiped out in 2015, losing most of their Parliamentary seats to the Conservatives. But Cameron also needed to ensure that he won in Parliamentary seats where UKIP threatened him as a result of their far right and anti-EU agenda. To do this, the Conservative Party’s manifesto in the 2015 election included various right wing agendas – and a commitment to hold a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU. Before the 2015 election, most people were foreseeing another coalition Government which might have meant that Cameron could have shelved the Conservative commitment to a referendum saying that his coalition partners did not agree to it.

Whether Cameron gambled that he would be able to backtrack on the commitment or not, he probably also gambled that there would be a majority of people in the UK who would – in some cases – reluctantly support ongoing EU membership for economic reasons. Indeed, this had probably been the reason why the majority of those living in Scotland, the northern part of the UK, had voted against Scotland becoming independent in 2014 – a referendum that had seen all of the national UK parties unite against the Scottish National Party against breaking up the UK union. That the UK national parties had campaigned together on this left a bitter taste in Scotland against the UK Labour Party.

No one – not even Cameron – anticipated the result of the 2015 UK General Election. The Conservatives picked up most of the Liberal Democratic seats. It held its own against UKIP. And most importantly – the generally nice but not particularly effective leader of the Labour Party massively under-estimated the effects of UKIP in disadvantaged communities who were sold on extreme hate messages about immigration – and whilst that did not lead to Parliamentary seats for UKIP in the UK’s first past the post system – it meant that the potential Labour vote was split in many of the marginal seats, which therefore fell to the Conservatives. As well as this, the Scottish referendum led to the Labour Party being wiped out in Scotland – formerly a heartland of its support – which enabled Cameron to campaign on the Labour Party needing the support of the Scottish National Party to govern.

This set of circumstances was toxic for the Labour Party and led to the incoming Conservative Government having a small Parliamentary majority for the first time since the 1990s. This in turn meant that they had free reign to promote even more austere policies – leading in turn to even more alienation in disadvantaged communities reliant on the welfare support and state supported housing that the incoming Conservative Government was heavily cutting.

This then led to the EU referendum itself. On the one hand, there was Cameron and some of his Government campaigning to “Remain” in the EU. On the other, the “Leave” campaign was led by Boris Johnson, a member of Cameron’s cabinet, former London Mayor and generally considered by many to be using the campaign as a political platform for himself personally. The Leave campaign was also supported by various other members of the Conservative Government and by a small number of Labour MPs. Alongside this, UKIP ran its own campaign led by Nigel Farage.

From the outset, it was clear that the campaigns were mired in misinformation, misdirection and outright lies. The Remain campaign focused on extreme results of the UK voting to leave the EU – and because its predictions were increasingly stark – it lacked credibility. The extreme predictions issued by the Remain campaign meant that when “experts” presented the facts about the EU, they were largely seen as part of a conspiracy led by the Westminster elite and the bankers.

The Leave campaign simply lied throughout – in particular claiming that £350m was being spent per week on the UK’s EU membership – a blatant lie in that much of that £350m was returned to the UK anyway through rebate and spending on UK farming subsidies, UK academic institutions, infrastructure projects in UK disadvantaged areas and on other UK spending. The Leave campaign both said that the current EU subsidies would continue through the UK Government at the same time saying that the whole mythical £350m could be spent on the UK’s National Health Service. The fantasy nature of this claim has led some to suggest that Boris Johnson never expected anyone would take the claim seriously, that his Leave campaign would win or that he would then be expected to deliver on it.

The Leave campaign also made bold statements about immigration which became the central issue in the campaign. Immigration from inside the EU (subject to the free movement of peoples within the EU) and outside the EU (subject already to UK Government policy) became conflated. The flames were further added to by the overtly racist campaign fought by Nigel Farage which culminated in a billboard compared to Nazi propaganda from the 1930s showing Syrian refugees queueing from outside the EU to enter Slovenia with the words “Breaking Point”. Claims were also made by the Leave campaign and by UKIP that the UK would be flooded by Turkish immigrants when Turkey becomes an EU member – clearly not on the cards at all at the moment – but this allowed these campaigns to reignite fears in the UK about the “Turk” reminiscent of Ottoman times. Both the Leave and UKIP campaigns were characterised by hate and fear, meaning that it became acceptable for racist and Islamophobic sentiments to be expressed online and elsewhere – sentiments that right thinking people in the UK thought had been eradicated from our national consciousness.

Whilst Conservatives voters might have been evenly split between Remainers and Leavers – and probably their minds had been made up years ago, a majority of Labour voters voted to Remain. The Labour Party, led by Jeremy Corbyn, who had been elected following Labour’s defeat in the 2015 election by a large majority of a Labour Party membership that had significantly grown because Corbyn had stood for election. Corbyn’s history in the Labour Party had long been opposition to neo-liberal supporting Governments of Blair and Brown in the 2000s, and this meant that those Labour Party members who supported him supported him because he represented a substantially different approach to the Blairite Governments. However, whilst the Labour Party membership has significantly grown under him and he has successfully galvanized the organised trade union labour movement and many people on the left who want an alternative to neo-liberalism, his appeal has not yet extended far outside this coterie. Crucially, he currently had very limited appeal within the disadvantaged communities who are not part of organised labour but who should be part of the Labour Party’s constituency.

I have to point out that I am on dodgy ground when I talk about Corbyn. Most of my friends avidly support him and see him as the saviour of socialism in the UK (much like Syriza in Greece). I have been a lifelong Labour Party member and I didn’t vote for him in the leadership contest. As a democrat, I have tried to support his leadership, but my view is that he will lose us the next General Election heavily if he remains our leader. Sadly this is not because of his policies – many of which I support – but it is (a) because the UK media is very neo-liberal and they have portrayed him as being extreme left wing – which is probably unfair, but which means he will not be elected and (b) because he does not have the charisma that is necessary to get politicians elected. He tells us that this is a new kind of politics which should not be reliant on charisma – but he just doesn’t come across as a leader.

Crucially in terms of the referendum, whilst he successfully campaigned to get Labour voters to support the Remain campaign on the basis of loss of workers’ rights – he had no message that chimed with disadvantaged communities.

In the end, it was these communities that swung the referendum vote narrowly to the UK leaving the EU. I knew this because I work in our state supported housing sector – and the chatrooms amongst tenants became lively about three weeks before the vote with people all saying that they were voting OUT. For them, they were responding to the messages that the UK is controlled by people in Europe; by concerns about swarms of migrants coming to the UK; and by perceptions of the political classes of all persuasions that they just want their vote but they are not really interested in what they think. These are people who have had their communities, their incomes and their livelihoods ripped apart for generations, and particularly so since the Cameron premiership in 2009. They are completely disempowered and they are the butt of hideous social stereotyping that they are wasters leeching off the state. They responded to the messages coming from the Leave side that an OUT vote would lead to us “taking back our country” and they saw the Leave side as being the rebellion they needed to make against UK democracy and politics. In most cases, they were probably unaware of the complexity of facts about the EU, and anyone trying to tell them the facts would not have been listened to and would have been seen as part of the political conspiracy against them. Any analysis of the results demonstrate that it was in their communities that the vote was lost – Sunderland and Hull – waste lands in the North East that have probably benefitted from much EU funding - and even South Wales – an area devastated in the 1980s by the loss of the Coal industry and which has never recovered – and which has had vast amounts of infrastructure funding from the EU – all voted heavily against EU membership.

Three particularly significant areas voted to remain in the EU. The first was Scotland which voted heavily to remain. This is significant in that it has already reignited the debate about Scottish independence – and it is probable that there will be a further referendum on that. The second was Northern Ireland. It is difficult to recount here the history of Northern Ireland – but the challenge there now is what they do about the border between the Republic of Ireland (still an EU member) and Northern Ireland. That it is now open was a key part of the agreement that brought the sectarian troubles in Northern Ireland to an end and if the border is closed – it is likely that this will lead to growing tensions. The third was London. There are tongue in cheek (?) proposals now that London should become an independent EU member, but the way that London is and how it is run is quite different from the rest of the UK, and it will be strange that the UK Government is based in a capital which still wants to be part of the EU.

A further challenge is that young people – who will be affected the most by this decision – voted heavily to remain in the EU whilst old people voted the other way. The tensions that this may cause are being exacerbated by news interviews with elderly people blathering on about how they want the country to be like how it used to be – stupid nonsense that young people – who want international options to be available to them – will find particularly galling.

The Leave campaign had absolutely no idea what they were going to do if they won. They probably anticipated that Cameron would hang about – meaning that they could blame him for the undoubted problems that will be caused by our exiting the EU – but he exited the stage the day after the vote (he’s still there but in a caretaker capacity until October and he will play no further significant role).

The Conservative Party will have a scrap about who becomes its leader (and therefore our Prime Minister) between now and October. The front runner is Boris Johnson because he clearly has electoral clout – but the Conservatives don’t like people who bring their leaders down – and it’s anyone’s guess as to whether he will win. My view is he will. He – or whoever becomes their leader – may call a General Election in order to ensure electoral support for their forward programme, not least because their main opposition – the Labour Party – are in disarray and not equipped to fight an election (a chunk of the Shadow Cabinet have resigned today amidst concerns about Corbyn’s leadership in the referendum).

Whoever becomes the UK Prime Minister will have a lot to deal with. The process of exiting the EU will be very arduous – much of our legislation is tied up in laws that we have agreed that were drawn up in Europe – and all of that will have to be rewritten. There are fears that workers’ and other rights that come to us through EU legislation will be watered down by a far right neo-liberal Conservative Government.

There will be the small matter of the UK negotiating trade deals with the EU and with the rest of the world. The UK’s trade treaties are through the EU and each will have to be individually negotiated (and the chances are that non-EU countries will want to know what our access to the EU is before they agree what deal they want to make with us).

There is a constitutional crisis growing in our relationship with Scotland who are saying that they may look for legal means to block our exit from the EU and that they will hold a second independence referendum. There will be a similar constitutional crisis in Northern Ireland regarding their border with the Republic of Ireland.

All of this is taking place against a backdrop of an uncertain economic future. It’s difficult to say what the economic consequences will be. Currently the pound has taken a hammering, the FTSE stock market is down, and UK PLC has had its triple AAA rating downgraded to negative. This may all change but it is too soon to say. As I understand it, the Brexit vote has had a damaging global effect – and actually markets are very difficult to predict. Our economic future may depend on how well the EU bounces back from this vote. In the UK, we are hearing about various far right groups in European countries also calling for an exit vote, and if that has traction – the UK may have damaged all European economies – but then in the UK, the news we hear is via a very right wing media.

It is also taking place against a backdrop of a lot of hate and fear and it is very difficult to say how that will turn out. There are currently numerous accounts on the internet of hostility towards non-white people and it may be the case that the far right extremes to which the Leave and UKIP campaigns went have opened a nasty pandora’s box that will be difficult to close.

The general story of what is going on in the UK is changing day by day and things may have dramatically changed in the next week. However, ultimately what all of this has exposed is that the fundamental flaw of neo-liberal western democracies – that they solely exist to support the middle income earners and that they ignore the 30% of low income earners and treat them as a problem to be policed – means that when asked to do something that the “educated” take as read – they are more than likely to say “up yours”. Unless neo-liberal western democracies can sort this problem out – very challenging in that neo-liberal capitalism will only permit minor deviations from its dictats (ask the Greeks) - then the underclass will do the same again possibly in some other way with potentially even worse consequences.

Before sending this, I asked a friend to take a look at it. As well as commenting that the Corbyn situation may change in the near future (this is a fast moving situation), he commented that “I'm not sure I would pin the referendum result quite so much on the post-industrial lost Labour heartlands. That was one among several factors – for example - we could look at the failure of the Conservative leadership to carry its vote past 42% as a massive rejection of Cameron and the party's inclusive side”.

Oh well – as I say – there are many perspectives on what’s going on!!!